Calling Bullsh*t on the Facebook Governance Vote

April 24, 2009

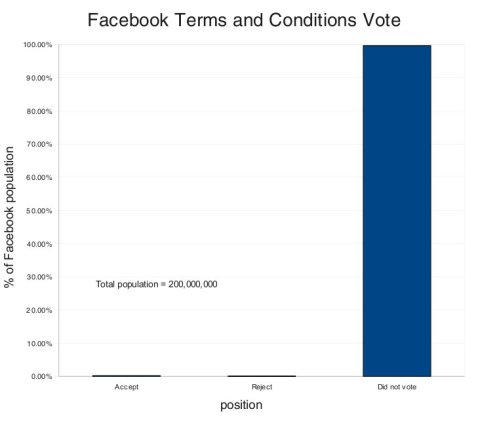

Well, Facebook users’ votes on the proposed Terms and Conditions are in – all 650,000 of them – and the company is pleased to report that 75% of the voters approved!

Hang on a moment, though – they only got 650,000 votes? I thought they wanted 30% of the Facebook user population to participate…

Since Facebook claims over 200,000,000 users – 650K is less than one third of one percent. Thirty percent would have been 60 million votes, not a measly 650 thousand.

That’s as if the United States held a national vote to reform the constitution and only the state of Montana voted…And then somebody described the election as a success.

In fact, since only 75% – or 450,000 of the 650,000 voters actually approved of the new T and C, it is more accurate to say that less than one quarter of one percent of the Facebook population supports this proposal.

So the equivalent in a U.S. election would be if the entire population of Memphis, Tennessee voted in favor of amending the constitution; the population of Spokane, Washington voted against the amendment; and the rest of the country just sat it out on the sidelines.

Since Facebook spokes-persons seem to indicate that the company intends to accept this vote as a sufficient mandate for adopting the new T and C, they are turning my snarky twilight zone scenario into a reality.

Here’s Facebook’s chart of the results (as re-published on the LA Times’ Technology blog):

…and here’s my chart of the same results (sorry for the fuzzy image – feel free to take 5 minutes and bake your own if you want a better one):

Such a woeful mockery would be even funnier if it weren’t so sad. Go, go, gadget, democracy!

I draw two conclusions:

1. Facebook has been hoisted by their own petard and they probably deserve whatever they get. This was a well-intentioned – but nevertheless naive – stunt from the beginning. It’s unfortunate that nobody at FB saw fit to back up all the rhetoric of user-generated revolution with a more meaningful participatory process.

2. Legitimate democracy is really, really hard. It doesn’t matter if it’s online or not. It’s not as simple as just holding a vote and hoping everyone will show up. It’s also not as simple as saying that the Facebook users were irresponsible because they didn’t show up. You have to build a culture of democracy in order to support democratic institutions like elections. That doesn’t happen overnight and it may be that a population like the users of Facebook isn’t sufficiently organized or engaged to begin that process.

The SF Chron reports that Gavin Newsom loudly declared his candidacy for governor via social media services like Facebook and Twitter yesterday.

In his speech Newsom promised “to spin CA to the future.”

Ugh.

Welcome to the sad reality of post-Obama politics in the U.S., where every candidate will succumb to the temptation to imitate the form and style of the OFA campaign without capturing the substance.

If Newsom is any indication, many of these candidates will fall flat on their faces – repeatedly – in the process.

Somebody get this man a new speech writer.

(updated: April 24, 2009 )

New Pew Survey: The Internet in Campaign 2008

April 16, 2009

The crazy-productive folks at Pew’s Internet and American Life project have a new survey published looking at The Internet’s Role in Campaign 2008.

There’s a lot of fun results to mine for anybody interested in political news consumption, participation and engagement via the Internet. I still need to read it more closely, but some of my favorite sound-bites so far:

- ~20% of those surveyed posted political commentary or content online

- ~20% of those surveyed reported seeking news sources that challenged their point of view

- A handy chart comparing where self-identified democrats and republicans get their online news. Statistically significant differences are marked with a “^” (Hint: look at CNN, Fox, Radio, and the Internet). Caveat: see my methodological comments below before interpreting this too deeply.

- This staggering time-series graph illustrating the decline of newspapers as a primary source of political news over the past 10 years or so (respondents were only allowed to mention their top two sources of news)

On a methodological note, it’s interesting that the surveyors chose to conduct the survey via land-line telephones only.

Some of you might recall that Pew also published some really interesting data in the middle of the campaign season suggesting that cell-only voters are disproportionately young, democratic, and Internet users.

Despite the fact that the surveyors weighted their results to try to reflect the demographics of telephone users in the U.S. as a whole, I take that to imply that the numbers in this latest survey should provide a conservative estimate the total Internet use in the population as a whole. At the same time, I think it undermines some of the comparisons between democratic and republican voters based on the land-line only data.

Development Industry Fail

April 14, 2009

USA Today has a really frustrating story about the UN’s abusive misuse of USAID funds for reconstruction projects in Afghanistan.

Basically, if you can think up a malicious way to screw up a development project, the UN probably did it. They built bridges that weren’t stable; “fixed” banks to make their basements leaky; and even siphoned funds into off-shore accounts.

USA Today includes a handy PDF of the USAID report.

For anyone who’s read James Ferguson’s classic The Anti-Politics Machine, this may all sound eerily familiar. Ferguson is a Cultural Anthropologist who teaches at Stanford. While the book is pretty heavy in the social theory department (if you don’t like Foucault, don’t even go there…), it chronicles how systematic failures occur as a consistent by-product of global governance and development organization interventions in the Global South.

This particular catastrophe is a totally different kind of failure than Ferguson talks about, but I think there’s a fantastic study to be done looking at how graft has become a systematic by-product of US interventions in the War on Terror in Afghanistan and Iraq.

We’ve gotten accustomed to passing off this kind of thing as a symptom or consequence of the Bush administration, but the problem with that explanation is that the phenomenon has replicated across such different bureaucracies and contexts. This is not just a few bad apples, it’s a series of institutions that unintentionally – but consistently – create opportunities for abuse.

The IMF Reloaded…Remixed

April 10, 2009

Tony Curzon Price has a thoughtful piece at Open Democracy in which he examines what he calls The G20’s sins of commission.

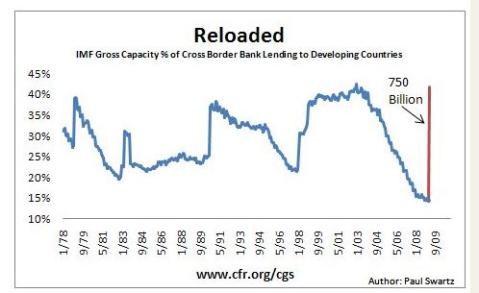

I’m interested in a whole bunch of angles that Price explores, but the money shot for all you global governance and development geeks out there is a graph Curzon Price recycles from Paul Swartz at Council on Foreign Affairs Geo-Graphics blog:

Curzon Price goes on to use the graph to make an interesting (and important) claim about the implications of China’s newfound romance with the IFI’s and global regulation.

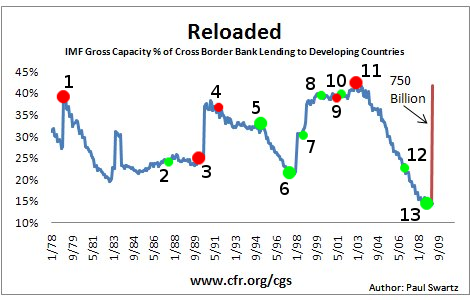

I, on the other hand, thought it would be kind of fun to play with the graph to try to get a better sense of what may have driven these changes in the IMF’s role over time. Since Swartz doesn’t share the data or source for his graphic, I’m reduced to hacking around with the .jpg in the GIMP (which made for a really fun distraction during a meeting the other day). Apologies for the resulting visual clutter, but here’s the same graph with some new knobs and bits. The bigger dots correspond to the events that accompanied the biggest shifts:

- Margaret Thatcher elected: May 1979

- Black Monday: Dec 1987

- Berlin Wall taken down: November, 1989

- Soviet Union Collapses: December 8, 1991

- Mexican Peso crisis: Dec 1994

- Asian Financial crisis: July 1997

- Brazil devalues the Real: Jan 1999

- Dot-com bubble bursts: March 10, 2000

- September 11, 2001

- Argentine debt default: Dec 2001

- US invades Iraq: March 20, 2003

- Brazil and Argentina pay off IMF debts: Dec. 2005

- Global Recession: October 2008

Some of the things I thought might correlate with sudden changes in the global weight of IMF lending – such as Black Monday (2); the Dot-com bubble burst (8); Argentina and Brazil paying off their debts (12) – didn’t seem to matter at all.

Others – such as Thatcher’s (and Reagan’s) election (1); the Mexican Peso crisis (5); and the 1-2 combo of the Asian (6) and Brazilian (7) financial crises – appear magnified when seen through this lens.

Most intriguing to me is the long steep slide that occurs following September 11, 2001 (9). My inclination is to explain that as the result of a perfect storm that combined the eroding credibility of the IMF (Joe Stiglitz, eat your heart out!) and a real estate derivative and petro-dollar fueled explosion of private lending world-wide. No matter how you slice it, though, there’s no denying that the world financial system has gone through some exceptionally dramatic changes in the last ten years.

Other than that, I don’t have a flashy Theory of Everything to explain all the data here. Heck, as I said, I don’t even have the data. Nevertheless, it’s fun to speculate.

Google and Market Failure: Think Wal-Mart, Not Microsoft

April 6, 2009

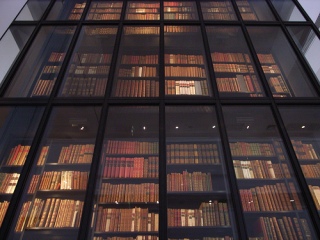

As in just about all the coverage I’ve seen of the Google Books deal with the Author’s Guild,

Friday’s NY Times story raises the familiar specter of Google-as-monopolist. This continues the longer-term trend of tarring the Mountain View, CA based firm with the same brush as it’s older, bigger, and more widely-distrusted rival from Redmond, WA. I’d like to point out a problem with this storyline that stems from the nature of the particular terms of the agreement.

In my mind, the nastiest and most inexplicable aspect of this agreement is not the bare fact that Google is about to buy the rights to a massive proportion of the world’s books. That has been a long time coming and is not a surprise. As many have pointed out, it could, in principle, lead to price manipulations when Google turns around to sell access back to libraries. However, I suspect we won’t see anything like that. Google’s lawyers aren’t stupid – they know that the Justice Department will be hot on their trail as soon as they get the faintest whiff of something like this. They will not want to let this happen if they can help it.

No, as I understand it, the truly nefarious part of the agreement preserves Google’s right to pay the same rate for licenses that publishers might offer to a hypothetical Google competitor in the future. This means that Google has effectively cornered the market for buying digital books – putting it in a position to shape the market to its liking in a way that looks much less evil to consumers.

The likely outcome is that buyers of access to Google Books won’t necessarily pay a premium price as they would with a typical monopolist. Instead, it is the organizations that sell rights to the books to Google in the first place who will be paid less than they would in a more competitive retail market.

Back in the 1930’s, the industrial economist Joan Robinson termed this kind of market failure a “monopsony.” The ideal typical form of monopsony arises in situations where the market for a particular good only has one buyer. This monopsonistic buyer is able to manipulate prices in much the same way that a monopolistic vendor would. The result is a market where the pricing mechanism fails to reflect supply and demand, perpetuating distortions and the breakdown of all the nice side effects that come along with a working market such as quality control, incentives to innovate, and adequate compensation for the producers of the goods in question.

Monopsony makes for less exciting headlines because it does not threaten consumers. Monopsonistic retailers slowly suck profits from their suppliers, forcing them to accede to their demands through the threat of massive revenue losses. The paradigmatic examle of a monopsonist in recent years has been Wal-Mart. The giant firm gets low prices for consumers by manipulating the prices of vendors (and by systematically undermining the labor market, but that’s another story). As soon as Wal Mart threatens to stop carrying their product, a seller has little bargaining leverage since they cannot afford to lose such a massive customer.

At least one person (who I don’t feel comfortable naming or quoting directly without permission) in the Berkman Center’s cyberlaw clinic assures me that the terms of Google’s agreement with the Author’s Guild are not totally clear on this point. Nevertheless, the fact that such an interpretation is not inconsistent with the text of the agreement should be reason enough to worry anyone who reads, writes, buys, or sells books.

subscribe to my feed

subscribe to my feed