The 2012 Obama campaign: Big Data Analysis and Gamification?

March 18, 2012

As the Republican presidential candidates continue to duke it out in contentious primary elections around the country, I’ve started to notice the increasingly public signs that the Obama campaign is gearing up for battle. Not surprisingly, I tend to focus on the Obama re-election team’s uses of digital technologies, where a number of shifts may result in important changes for both the voter-facing and internal components of the Obama For America’s (OFA) digital operations. I started writing this post with the intent of reviewing some of the recent news coverage of the campaign, but it turned into a bit more of a long-form reflection about the relationship between the campaign’s approach to digital tools might mean for democracy.

OFA 2.0: Bigger, Faster, & Stronger (Data)

A fair amount of media coverage has suggested that the major technology-driven innovations within OFA and the Democratic party this election cycle are likely to consist of refined collection and analysis collection of vast troves of voter data as opposed to highly visible social media tools (such as My.BarackObama.com) that made headlines in 2008.

As Daniel Kreiss & Phil Howard elaborated a few years ago, database centralization and integration became core strategic initiatives for the Democratic National Committee after the 2000 election and the Obama campaign in 2008. These efforts have been expanded in big ways during the build-up to the current campaign cycle.

According to the bulk of the (often quite breathless) reporting on the semi-secretive activities of the 2012 Obama campaign, the biggest and newest initiatives represent novel applications of the big data repositories gathered by the campaign and its allies in previous years. These include the imaginatively named “Project Narwhal” aimed at correlating diverse dimensions of citizens’ behavior with their voting, donation, and volunteering records. There is also “Project Dreamcatcher,” an attempt to harness large-scale text analytics to facilitate micro-targeted voter outreach and engagement.

For a vivid example of what these projects mean (especially if you’re on any of the Obama campaign email lists), check out ProPublica’s recent coverage comparing the text of different versions of the same fundraising email distributed by the campaign two weeks ago (the narrative is here and the actual data and analysis are here).

(Side note: in general, Sasha Issenberg’s coverage of these and related aspects of the campaigns for Slate is great.)

What’s Next: “Gamified” and Quasi-open Campaign App Development

As the Republicans sort out who will face Obama in November, OFA will, of course, roll-out more social media content and tools. In this regard, last week’s release of heavily hyped “The Road We’ve Traveled” on YouTube was only the beginning of the campaign’s more public-facing phase.

The polished, professional video suggests that OFA will build on all of the social media presence and experience they built during and the last cycle as well as over the intervening years of Obama’s administration.

Less visible and less certain are whether any truly new social media tools or techniques will emerge from the campaign or its allies. Here, there are two recent initiatives that I think we might be talking about more over the course of the next six months.

The first of these started late last year, when OFA experimented with a relatively unpublicized initiative called “G.O.P. Debate Watch.” Aptly characterized by Jonathan Easley in The Hill as a “drinking game style fundraiser” the idea was that donors committed to give money for every time that a Republican candidate uttered particular, politicized keywords identified ahead of time (e.g. “Obamacare” or “Socialist”).

In its attempt to combine entertainment and a little bit of humor with small-scale fundraising, G.O.P. Debate Watch fits with a number of OFA’s other techniques aimed at using digital initiatives to lower the barriers to participation and engagement. At the same time, it incorporates much more explicit game-dynamics, setting it apart from earlier efforts and exemplifying the wider trend towards commercial gamification.

The second initiative, which only recently became public knowledge, has just begun with OFA opening a Technology Field Office in San Francisco last week.

The really unusual thing about the SF office is that it appears as though the campaign will use it primarily to try to organize and harness the efforts of volunteers who possess computer programming skills. This sort of coordinated, quasi-open tool-building effort is completely unprecedented, especially within OFA, which has historically pursued a secretive and closed model of innovation and internal technology development.

If the S.F. technology field office results in even one or two moderately successful projects – I imagine there will be a variety of mobile apps, games, and related tools that it will release between now and November – it may give rise to a wave of similar semi-open innovation efforts and facilitate an even closer set of connections between Silicon Valley firms and OFA.

Is This What Digital Democracy Looks Like?

I believe that the applications of commercial data-mining tools and gamification techniques to political campaigns have contradictory implications for democracy.

On the one hand, big data and social games represent the latest and greatest tools available for campaigns to use to try to engage citizens and get them actively involved in elections. Given the generally inattentive and fragmented state of the American electorate, part of me therefore believes that these efforts ultimately serve a valuable civic purpose and may, over the long haul, help to create a vital and digitally-enhanced civic sphere in this country.

At the same time, it is difficult to see how the OFA initiatives I have discussed here (and others occurring elsewhere across the U.S. political spectrum) advance equally important goals such as promoting cross-ideological dialogue, deliberative democracy, voter privacy, political accountability, or electoral transparency. (Along related lines, Dan Kreiss has blogged his thoughts about the 2012 Obama campaign and its embodiment of a certain vision of “the technological sublime.”)

All the database centralization, data mining, and gamified platforms for citizen engagement in the world will neither make a dysfunctional democratic government any more accountable to its citizens; erase broken aspects of the electoral system; nor generate a more deeply democratic and representative networked public sphere. Indeed, these techniques have generally been used to grow the bottom line of private companies with little or no concern for whether or not any broader public goods are created or distributed. Voters, pundits, President Obama, and the members of his campaign staff would all do well to keep that in mind no matter what happens this Fall.

Calling Bullsh*t on the Facebook Governance Vote

April 24, 2009

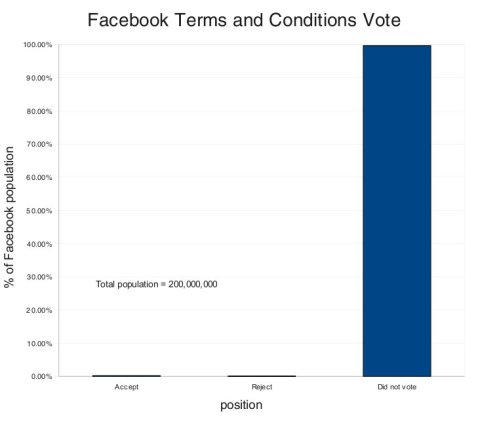

Well, Facebook users’ votes on the proposed Terms and Conditions are in – all 650,000 of them – and the company is pleased to report that 75% of the voters approved!

Hang on a moment, though – they only got 650,000 votes? I thought they wanted 30% of the Facebook user population to participate…

Since Facebook claims over 200,000,000 users – 650K is less than one third of one percent. Thirty percent would have been 60 million votes, not a measly 650 thousand.

That’s as if the United States held a national vote to reform the constitution and only the state of Montana voted…And then somebody described the election as a success.

In fact, since only 75% – or 450,000 of the 650,000 voters actually approved of the new T and C, it is more accurate to say that less than one quarter of one percent of the Facebook population supports this proposal.

So the equivalent in a U.S. election would be if the entire population of Memphis, Tennessee voted in favor of amending the constitution; the population of Spokane, Washington voted against the amendment; and the rest of the country just sat it out on the sidelines.

Since Facebook spokes-persons seem to indicate that the company intends to accept this vote as a sufficient mandate for adopting the new T and C, they are turning my snarky twilight zone scenario into a reality.

Here’s Facebook’s chart of the results (as re-published on the LA Times’ Technology blog):

…and here’s my chart of the same results (sorry for the fuzzy image – feel free to take 5 minutes and bake your own if you want a better one):

Such a woeful mockery would be even funnier if it weren’t so sad. Go, go, gadget, democracy!

I draw two conclusions:

1. Facebook has been hoisted by their own petard and they probably deserve whatever they get. This was a well-intentioned – but nevertheless naive – stunt from the beginning. It’s unfortunate that nobody at FB saw fit to back up all the rhetoric of user-generated revolution with a more meaningful participatory process.

2. Legitimate democracy is really, really hard. It doesn’t matter if it’s online or not. It’s not as simple as just holding a vote and hoping everyone will show up. It’s also not as simple as saying that the Facebook users were irresponsible because they didn’t show up. You have to build a culture of democracy in order to support democratic institutions like elections. That doesn’t happen overnight and it may be that a population like the users of Facebook isn’t sufficiently organized or engaged to begin that process.

The SF Chron reports that Gavin Newsom loudly declared his candidacy for governor via social media services like Facebook and Twitter yesterday.

In his speech Newsom promised “to spin CA to the future.”

Ugh.

Welcome to the sad reality of post-Obama politics in the U.S., where every candidate will succumb to the temptation to imitate the form and style of the OFA campaign without capturing the substance.

If Newsom is any indication, many of these candidates will fall flat on their faces – repeatedly – in the process.

Somebody get this man a new speech writer.

(updated: April 24, 2009 )

New Pew Survey: The Internet in Campaign 2008

April 16, 2009

The crazy-productive folks at Pew’s Internet and American Life project have a new survey published looking at The Internet’s Role in Campaign 2008.

There’s a lot of fun results to mine for anybody interested in political news consumption, participation and engagement via the Internet. I still need to read it more closely, but some of my favorite sound-bites so far:

- ~20% of those surveyed posted political commentary or content online

- ~20% of those surveyed reported seeking news sources that challenged their point of view

- A handy chart comparing where self-identified democrats and republicans get their online news. Statistically significant differences are marked with a “^” (Hint: look at CNN, Fox, Radio, and the Internet). Caveat: see my methodological comments below before interpreting this too deeply.

- This staggering time-series graph illustrating the decline of newspapers as a primary source of political news over the past 10 years or so (respondents were only allowed to mention their top two sources of news)

On a methodological note, it’s interesting that the surveyors chose to conduct the survey via land-line telephones only.

Some of you might recall that Pew also published some really interesting data in the middle of the campaign season suggesting that cell-only voters are disproportionately young, democratic, and Internet users.

Despite the fact that the surveyors weighted their results to try to reflect the demographics of telephone users in the U.S. as a whole, I take that to imply that the numbers in this latest survey should provide a conservative estimate the total Internet use in the population as a whole. At the same time, I think it undermines some of the comparisons between democratic and republican voters based on the land-line only data.

the hyperinformed electorate?

November 6, 2008

While Henry Farrell probably didn’t intend this CT post from last week the way I’m going to respond to it, I still think it’s interesting to consider his suggestion that election junkies had bigger, faster, and better access to news and information during this campaign.

Eszter Hargittai’s research would suggest that for most of us it’s not how much information the Internet makes available, but rather the accessibility of the information that counts. So was the information Henry talks about accessible?

The best answer probably depends on who you ask. Like so many others, I loved me some Nate Silver simulations throughout the last few weeks, but I don’t pretend to understand the ins and outs of Silver’s computational wizardry. Similarly, I religiously followed the composite polls at Pollster.com, Daily Kos, and RCP, but balk at the fine points of curve smoothing and best fit graphing techniques.

In this sense, I wonder how Joe-Internet-Surfer coped with the Habermasian equivalent of TMI?

NO on CA Propositions 4 and 8

November 4, 2008

I’ve noticed an up-tick in the searches and hits on an old post I did about California propositions that were on a ballot in June, so I figured I’d write a quick post with my positions on the most important measures this November.

To be brief and direct: Vote NO on Propositions 4 and 8.

Get more information and more endorsements from Calitics (partisan) and from smartvoter.org (non-partisan).

subscribe to my feed

subscribe to my feed