The IMF Reloaded…Remixed

April 10, 2009

Tony Curzon Price has a thoughtful piece at Open Democracy in which he examines what he calls The G20’s sins of commission.

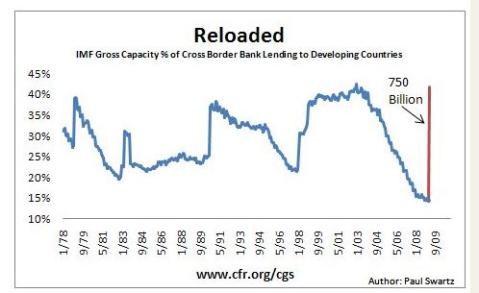

I’m interested in a whole bunch of angles that Price explores, but the money shot for all you global governance and development geeks out there is a graph Curzon Price recycles from Paul Swartz at Council on Foreign Affairs Geo-Graphics blog:

Curzon Price goes on to use the graph to make an interesting (and important) claim about the implications of China’s newfound romance with the IFI’s and global regulation.

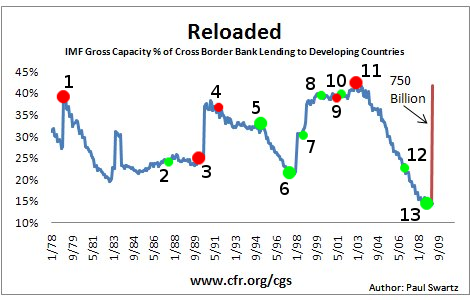

I, on the other hand, thought it would be kind of fun to play with the graph to try to get a better sense of what may have driven these changes in the IMF’s role over time. Since Swartz doesn’t share the data or source for his graphic, I’m reduced to hacking around with the .jpg in the GIMP (which made for a really fun distraction during a meeting the other day). Apologies for the resulting visual clutter, but here’s the same graph with some new knobs and bits. The bigger dots correspond to the events that accompanied the biggest shifts:

- Margaret Thatcher elected: May 1979

- Black Monday: Dec 1987

- Berlin Wall taken down: November, 1989

- Soviet Union Collapses: December 8, 1991

- Mexican Peso crisis: Dec 1994

- Asian Financial crisis: July 1997

- Brazil devalues the Real: Jan 1999

- Dot-com bubble bursts: March 10, 2000

- September 11, 2001

- Argentine debt default: Dec 2001

- US invades Iraq: March 20, 2003

- Brazil and Argentina pay off IMF debts: Dec. 2005

- Global Recession: October 2008

Some of the things I thought might correlate with sudden changes in the global weight of IMF lending – such as Black Monday (2); the Dot-com bubble burst (8); Argentina and Brazil paying off their debts (12) – didn’t seem to matter at all.

Others – such as Thatcher’s (and Reagan’s) election (1); the Mexican Peso crisis (5); and the 1-2 combo of the Asian (6) and Brazilian (7) financial crises – appear magnified when seen through this lens.

Most intriguing to me is the long steep slide that occurs following September 11, 2001 (9). My inclination is to explain that as the result of a perfect storm that combined the eroding credibility of the IMF (Joe Stiglitz, eat your heart out!) and a real estate derivative and petro-dollar fueled explosion of private lending world-wide. No matter how you slice it, though, there’s no denying that the world financial system has gone through some exceptionally dramatic changes in the last ten years.

Other than that, I don’t have a flashy Theory of Everything to explain all the data here. Heck, as I said, I don’t even have the data. Nevertheless, it’s fun to speculate.

The Price of Globalist Unilateralism

December 19, 2008

ASEAN may go ahead with once-scrapped plans to create an Asian Monetary Fund as an alternative to the IMF.

Seems to me like a redundant effort that only makes sense given the extent to which the IMF does not respond effectively to the needs of the majority of its member states.

Multilateralism falls apart if you don’t cultivate it in good faith.

Brazil, the IMF’s A-List, and Currency Swaps

October 31, 2008

Following up on my earlier post in response to this Guardian story that offered an un-attributed claim that Brazil was appealing to the IMF for loans, it now looks like the Guardian wasn’t so much wrong as just a little inaccurate fuzzy on the details. Whereas the original Guardian story had spun the situation as though the wealthy nations of the Global South had come to D.C. with hat in hand, it looks like a totally different situation is in fact unfolding. The new liquidity fund is meant to offer stable “A-list” economies of the South the chance to strengthen their currency reserves in the event that foreign investment flows continue to run dry. According to the WSJ:

The IMF’s new program, called the Short Term Liquidity Facility, would be used largely to pad a country’s reserves, which could help the recipient defend its currency. But the funds could also be used to help recapitalize banks or cover import bills.

The IMF plan is its clearest recognition that its insistence on tough conditions is driving away potential borrowers that might need its help. But the new plan also puts the IMF in the position of deciding who can have money with few strings attached, and who can’t.

The attempt to draw a bright clear line between “responsible” and “irresponsible” borrowers is certainly new. It will be interesting to see where it leads.

Back to Brazil, though.

Reuters (via the Economic Times of India) actually found someone in Brasilia to do some reporting and added the following:

Brazil welcomes a new liquidity fund proposed by the International Monetary Fund to help emerging markets but does not see a need to draw on the funds for now, a source close to President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva said on Wednesday.

“I don’t know if we will draw (on the fund) in the future. But we don’t need the money now,” the source said on condition of anonymity. The IMF board is considering a proposal for the Fund on Wednesday and an announcement is expected later in the day.

The Folha de São Paulo added even more critical details in its coverage, also noting that the IMF actions came in conjunction with an announcement that the US Federal Reserve will begin offering Brazil currency swaps at no cost in an effort to help the Lula government pump liquidity into the national economy:

The Central Bank [of Brazil] noted that, “these central banks of emerging economies with responsible fiscal policies and systemic importance,” will now be included in the global network of currency swaps.

The central banks of Australia, Canada, the Euro Zone, Denmark, the U.K., Norway, New Zealand, Sweden, Switzerland, and the U.S. Federal Reserve are currently part of that network. (my translation).

The Folha’s account was reiterated by Bloomberg as well, although the New York-based financial news agency did see fit to print at least one offensive, infantilizing quote that portrayed the poor countries of the world as naughty elementary school students:

“The Fed is there to support large emerging markets that have done their homework over the past several years like South Korea, Brazil, Singapore and Mexico,” said Alonso Cervera, a Latin America economist with Credit Suisse Group in New York.

If the central bankers of the world just needed to do their homework in order to build stable economic systems, I’d like to think that Alan Greenspan wouldn’t have had such a hard time.

Anyhow, if I understand this correctly, the actions taken by the IMF and the Fed signal an effort to treat these four middle income countries with an unprecedented level of parity in response to a crisis that has far exceeded anyone’s expectations. The implications for the post-election day Global Financial Summit are intriguing: will the members of the G22 now have a more substantive place at the bargaining table with an embattled Europe and U.S.? If so, will the Southern super-powers use their authority to defend the interests of their less well-off neighbors or will they merely seek a bigger slice of the pie?

IMF swoops in with cash, conditionalities

October 29, 2008

Iceland and Hungary are the first recipients of IMF loans as a result of the current global financial crisis.

In a sign of what’s to come, the Fund is already demonstrating its continued willingness to impose policy conditionalities on borrower states.

The Guardian has the story in Hungary:

This week the International Monetary Fund stepped in to stop any more investors from pulling their funds out of the country altogether. Hungary is now set to become the first EU state to receive an IMF lifebelt – of around €12.5bn.

The bail-out announcement received a mixed response in Budapest yesterday. “We have a credit noose around our necks,” declared the rightwing daily Magyar Hirlap, while another paper showed bundles of forint notes being sucked up by a cyclone.

“This is going to be tough,” said the tabloid Blikk, pointing out that a condition of the loan would be a 300bn forint cut in public spending, which will likely lead to high inflation and attacks on social benefits.

And the Financial Times covers Iceland:

The application will be presented to the IMF’s board on Thursday and the central bank said a condition attached to the loan was for a rate rise to 18 per cent.

The move reversed a 3.5 per cent rate cut announced just two weeks ago by David Oddsson, central bank governor, underlining the influence the IMF now has over policymaking in Iceland.

Brian Coulton, managing director at Fitch Ratings, the credit rating agency, said Iceland’s central bank had “no choice but to work very closely with the fund”.

While the policy conditionalities attached to the loans appear less extensive than the intrusive demands the IMF and World Bank used to place on its borrowers, the persistent willingness of the Fund to dictate borrower fiscal policy suggest that the D.C.-based institution has failed to learn from experience. IMF-sponsored structural adjustment policies implemented throughout the 1980’s and 90’s precipitated a string of fiscal crises in the economies of the Global South.

While I’ll have to dig around in the academic journals to assess whether there’s any evidence that IMF-loans caused later crises among borrower countries in the 80’s and 90’s, the historical record in places like Argentina, Mexico, and Brazil is pretty clear: in the process of imposing conditionalities had profound flaws that facilitated the collapse of otherwise strong currencies.

The obvious difference this time around is that the borrowers are in Europe – it will be interesting to see how this affects outcomes.

Global leaders <3 the IMF, but Brazil?

October 26, 2008

Didn’t see this story until after I had posted earlier today. The lede from the Guardian:

Asian and European leaders today called for more international regulation and a stronger role for the International Monetary Fund in response to the worst financial crisis since the 1930s.

No surprise there. All the questions I outline in my post below still apply.

Meanwhile, the story goes on to include at least the second mention I’ve seen that Brazil is considering going to the IMF for funds in response to the crisis.

The problem is there is no attribution for this assertion, which (if it were true) would constitute a major about-face for the Lula government and a big news item in Latin America’s most populous nation and most globally integrated economy.

So, did the author just make it up? I don’t know, but I can’t find any evidence to support his claim in the financial section of Brazil’s most reputable paper, the Folha de Sao Paulo. Similarly, other English language publications, such as the Christian Science Monitor, have run stories suggesting that Brazil is among the best prepared countries to weather the crisis in terms of its cash reserves.

Given the sensitivity of global markets right now, I hope the Guardian editors will consider investigating this rumor before it gets out of control. Bond rating agencies read this kind of stuff and they won’t like it even if it is just an irresponsible slip.

Reinventing the IMF?

October 26, 2008

With the continued decline of financial markets and the threat of radical destablization throughout the Global South, I suspect that a consensus view that the IMF must step in to ensure the solvency of developing countries is already spreading quickly among the punditocracy and major news outlets.

Given the weakened condition of wealthy states and corporations, the IMF will play a major role in any sort of multilateral bailout. Indeed the crisis presents an opportunity for the Fund to resurrect itself after a number of very, very bad decisions made in the Neoliberal 1980’s and 90’s finally came home to roost, bringing shame upon the organization and its ideas.

The question is what kind of an IMF will we get this time around? The critical work of Joseph Stiglitz, Ngaire Woods

, and others

has provided ample evidence that the Fund’s proclivities for anti-poor policies were not an accident, but a systematic result of the organization’s structure and culture.

Since 2002 (when such positions first gained widespread traction), there has been much talk of reform – a trend which will no doubt continue well past November’s Global Financial Summit – but precious little action.

The U.S. and Europe still retain a ridiculous share of the voting power within the IMF, World Bank, and the WTO, virtually guaranteeing that they will strong arm through whatever solutions they deem fit. While Ambassadors, Trade Representatives, and their ilk may talk a good game about promoting equality through increased multilateral liberalization, the bottom line is that truly equitable trade will not come about without a substantial sacrifice by the traditional “Great Powers” of the West. The recent trend of the U.S. and E.U. pursuing absurd schemes to evade accountability and transparency by undermining global forums also belies any rhetoric of good will.

Does the IMF have what it takes to bring about a true shift in the underlying structures of the global financial system? I doubt it, but it will be revealing to see just how hard Dominique Strauss-Khan (if he holds onto his job now that he has officially held onto his job despite a sex scandal) and his colleagues will try.

Sebastian Mallaby on the Bretton Woods Redux plans

October 20, 2008

Mallaby’s editorial in today’s WP echoes some of the broad points I tried to make in my last post, but goes into greater detail on some plausible concrete outcomes from the proposed Bretton Woods Redux.

The key points are in the following paragraphs:

So what might a new Bretton Woods conference usefully do? Well, it could reform the IMF, which has evolved from its original role into a rescue fund for collapsing currencies. During the emerging market crises of a decade ago, the IMF was central to all the bailouts. Its status has since dwindled…

Reestablishing the IMF as the agreed provider of bailouts would be a worthwhile project. The IMF puts economic conditions on its loans while governments place political ones; we don’t want to revive the cronyism of the Cold War, when countries from Cuba to Zaire could pursue absurd policies and know they would be bailed out because they were strategically useful.

The irony is that Britain and France will be the first to resist a serious effort to revive the IMF. British Prime Minister Gordon Brown talks vacuously about giving the organization the role of creating an early-warning system for crises, even though this is what thousands of economic forecasters already try to provide. What Brown does not stress is that serious IMF reform needs to begin with the modernization of its board. Rising powers such as China and India deserve more say. Declining powers need to give up some influence — and that includes France and Britain.

Like I said, we’re heading for Doha all over again…

IMF attempts governance reforms and doesn’t get far

April 3, 2008

The Bretton Woods Project reports on recent efforts to democratize the voting structure at the IMF. Seems like the negotiations have successfully managed to get old wine into a new bottle. See the article for a detailed discussion of the proposed changes to the formulas used to calculate votes as well as some interested commentary from the officials involved in the process.

My favorite quote:

Ralph Bryant, a scholar at the Washington-based Brookings Institution, called the compromise pallid and inadequate: “The image to have in mind is that of a decades-old building in need of major repairs and renovation. The plumbing is ancient and badly needs updating. The roof is leaking in places. Termites have been found in the support joists in the basement. What steps are being recommended to renovate the building? What is on offer is, essentially, a fresh coat of paint in the entrance hallway and the fixing of some broken glass panes in the windows facing the street.”

That’s gotta be one of the snarkier soundbytes coming out of Brookings in a while. You tell ’em Ralph!

(Hat tip to the South Centre blog for the link)

subscribe to my feed

subscribe to my feed