The IMF Reloaded…Remixed

April 10, 2009

Tony Curzon Price has a thoughtful piece at Open Democracy in which he examines what he calls The G20’s sins of commission.

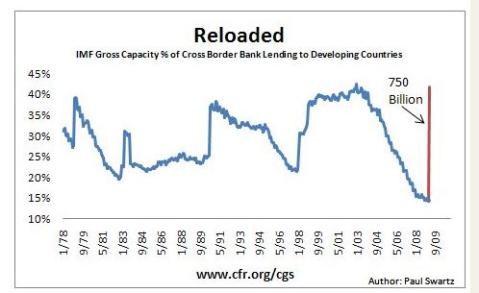

I’m interested in a whole bunch of angles that Price explores, but the money shot for all you global governance and development geeks out there is a graph Curzon Price recycles from Paul Swartz at Council on Foreign Affairs Geo-Graphics blog:

Curzon Price goes on to use the graph to make an interesting (and important) claim about the implications of China’s newfound romance with the IFI’s and global regulation.

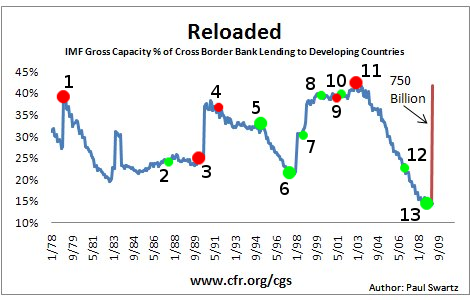

I, on the other hand, thought it would be kind of fun to play with the graph to try to get a better sense of what may have driven these changes in the IMF’s role over time. Since Swartz doesn’t share the data or source for his graphic, I’m reduced to hacking around with the .jpg in the GIMP (which made for a really fun distraction during a meeting the other day). Apologies for the resulting visual clutter, but here’s the same graph with some new knobs and bits. The bigger dots correspond to the events that accompanied the biggest shifts:

- Margaret Thatcher elected: May 1979

- Black Monday: Dec 1987

- Berlin Wall taken down: November, 1989

- Soviet Union Collapses: December 8, 1991

- Mexican Peso crisis: Dec 1994

- Asian Financial crisis: July 1997

- Brazil devalues the Real: Jan 1999

- Dot-com bubble bursts: March 10, 2000

- September 11, 2001

- Argentine debt default: Dec 2001

- US invades Iraq: March 20, 2003

- Brazil and Argentina pay off IMF debts: Dec. 2005

- Global Recession: October 2008

Some of the things I thought might correlate with sudden changes in the global weight of IMF lending – such as Black Monday (2); the Dot-com bubble burst (8); Argentina and Brazil paying off their debts (12) – didn’t seem to matter at all.

Others – such as Thatcher’s (and Reagan’s) election (1); the Mexican Peso crisis (5); and the 1-2 combo of the Asian (6) and Brazilian (7) financial crises – appear magnified when seen through this lens.

Most intriguing to me is the long steep slide that occurs following September 11, 2001 (9). My inclination is to explain that as the result of a perfect storm that combined the eroding credibility of the IMF (Joe Stiglitz, eat your heart out!) and a real estate derivative and petro-dollar fueled explosion of private lending world-wide. No matter how you slice it, though, there’s no denying that the world financial system has gone through some exceptionally dramatic changes in the last ten years.

Other than that, I don’t have a flashy Theory of Everything to explain all the data here. Heck, as I said, I don’t even have the data. Nevertheless, it’s fun to speculate.

The Price of Globalist Unilateralism

December 19, 2008

ASEAN may go ahead with once-scrapped plans to create an Asian Monetary Fund as an alternative to the IMF.

Seems to me like a redundant effort that only makes sense given the extent to which the IMF does not respond effectively to the needs of the majority of its member states.

Multilateralism falls apart if you don’t cultivate it in good faith.

Inequality in the Knowledge-Based Economy

December 17, 2008

I’m working on a short article about this topic and was crunching some World Bank Development Index numbers today.

The payoff for you, dear reader, is the following factoid of the day:

From 2000-2008, approximately $97 out of every $100 earned internationally from licenses or royalties was paid to a high income OECD country. In contrast, Latin American and Caribbean countries combined to earn $0.005 (yes, one half of one cent) out of that same $100.

Got that? $97 vs. $0.0o5!

The moral of the story: cheap laptops and broadband are only the tip of the iceberg.

Eat your heart out ICT4D community.

Brazil as Petro-economy

November 23, 2008

Ever since the announcement of the discovery of Brazil’s Tupi oil field earlier this year, I haven’t really taken the time to think about the political implications of the new-found reserves. This article from the Christian Science Monitor is suggestive in that regard. Unfortunately, the piece hews to a decidedly optimistic storyline about how the income will pay for new social welfare programs. That’s all well and good, but let’s take off the rose-tinted glasses long enough to consider at least a few of the less attractive alternatives.

I share the view that Brazil’s new-found oil wealth will bring about transformative changes within the country’s economy, its state, and its society. The infusion of cash will indeed open up untold opportunities for closing Brazil’s notorious wealth gap. It will also further entrench Petrobras – already one of the largest firms in the Global South – as a worldwide energy-production leader. To the extent that these opportunities are managed effectively, Brazil will gain in influence, wealth, and international prestige.

However, to the extent that the Petrobras windfall is managed poorly and generates unanticipated spillover affects, it could easily produce a catastrophe. The sudden surge in income will likely give Petrobras executives and investors even more political clout than they already have, leading to increased opportunities for corruption (already a neverending problem in Brazilian politics), graft, and nepotism within the state. Furthermore, only an immense amount of well-channeled political goodwill can prevent the expansion of Petrobras from encroaching on the political interests of Brazil’s other burgeoning industries and its most vulnerable citizens.

This is not about simple optimism or pessimism, but rather about the realities of imbalanced petro-economies. The reasons why other oil-rich nations have such a horrendous track-record in terms of political accountability, transparency, and inequality has a lot to do with the pressures that a burgeouning state-owned energy sector tends to place on the rest of the state and private sector. Just because Brazil has enjoyed sustainable growth and social progress since the mid 1990’s does not mean that it has somehow “advanced” beyond the point at which its oil might prove more troublesome than its worth.

Gearing up for the financial summit

November 10, 2008

Brace yourselves for a flurry of promises and diplomatic hand-waving as the world prepares for this weekend’s global financial summit.

The NYT reports that the G20 wants a bigger say in the global economy. Problem is, the global financial summit is not designed to achieve far-reaching structural changes of the sort G20 leaders such as Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva are seeking.

The European Network on Debt and Development suggests that Europe will bring lofty ambitions to the table as well, but precious little in the way of concrete mechanisms or meaningful procedural reforms to affect change.

My sense? Prepare for disappointment. As Aldo Caliari points out, the timing and form of President Bush’s economic summit is designed to undermine ongoing negotiations at Doha and avoid the transparent and multilateral approach of the United Nations. As such, the whole affair is looking depressingly similar to the original Bretton Woods meetings of 1944. Until the U.S. and Europe show the political maturity to surrender some authority and embrace a truly multilateral process we will get a lot of fluffy proclamations but few substantive changes.

Don’t get me wrong, I suspect that there will be some impressive sounding stuff that comes out of this weekend’s meetings. I have no reason to believe, however, that it will be anything like the kind of democratic, equitable sorts of reforms to global trade and finance that the world so deeply needs.

Brazil, the IMF’s A-List, and Currency Swaps

October 31, 2008

Following up on my earlier post in response to this Guardian story that offered an un-attributed claim that Brazil was appealing to the IMF for loans, it now looks like the Guardian wasn’t so much wrong as just a little inaccurate fuzzy on the details. Whereas the original Guardian story had spun the situation as though the wealthy nations of the Global South had come to D.C. with hat in hand, it looks like a totally different situation is in fact unfolding. The new liquidity fund is meant to offer stable “A-list” economies of the South the chance to strengthen their currency reserves in the event that foreign investment flows continue to run dry. According to the WSJ:

The IMF’s new program, called the Short Term Liquidity Facility, would be used largely to pad a country’s reserves, which could help the recipient defend its currency. But the funds could also be used to help recapitalize banks or cover import bills.

The IMF plan is its clearest recognition that its insistence on tough conditions is driving away potential borrowers that might need its help. But the new plan also puts the IMF in the position of deciding who can have money with few strings attached, and who can’t.

The attempt to draw a bright clear line between “responsible” and “irresponsible” borrowers is certainly new. It will be interesting to see where it leads.

Back to Brazil, though.

Reuters (via the Economic Times of India) actually found someone in Brasilia to do some reporting and added the following:

Brazil welcomes a new liquidity fund proposed by the International Monetary Fund to help emerging markets but does not see a need to draw on the funds for now, a source close to President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva said on Wednesday.

“I don’t know if we will draw (on the fund) in the future. But we don’t need the money now,” the source said on condition of anonymity. The IMF board is considering a proposal for the Fund on Wednesday and an announcement is expected later in the day.

The Folha de São Paulo added even more critical details in its coverage, also noting that the IMF actions came in conjunction with an announcement that the US Federal Reserve will begin offering Brazil currency swaps at no cost in an effort to help the Lula government pump liquidity into the national economy:

The Central Bank [of Brazil] noted that, “these central banks of emerging economies with responsible fiscal policies and systemic importance,” will now be included in the global network of currency swaps.

The central banks of Australia, Canada, the Euro Zone, Denmark, the U.K., Norway, New Zealand, Sweden, Switzerland, and the U.S. Federal Reserve are currently part of that network. (my translation).

The Folha’s account was reiterated by Bloomberg as well, although the New York-based financial news agency did see fit to print at least one offensive, infantilizing quote that portrayed the poor countries of the world as naughty elementary school students:

“The Fed is there to support large emerging markets that have done their homework over the past several years like South Korea, Brazil, Singapore and Mexico,” said Alonso Cervera, a Latin America economist with Credit Suisse Group in New York.

If the central bankers of the world just needed to do their homework in order to build stable economic systems, I’d like to think that Alan Greenspan wouldn’t have had such a hard time.

Anyhow, if I understand this correctly, the actions taken by the IMF and the Fed signal an effort to treat these four middle income countries with an unprecedented level of parity in response to a crisis that has far exceeded anyone’s expectations. The implications for the post-election day Global Financial Summit are intriguing: will the members of the G22 now have a more substantive place at the bargaining table with an embattled Europe and U.S.? If so, will the Southern super-powers use their authority to defend the interests of their less well-off neighbors or will they merely seek a bigger slice of the pie?

Reinventing the IMF?

October 26, 2008

With the continued decline of financial markets and the threat of radical destablization throughout the Global South, I suspect that a consensus view that the IMF must step in to ensure the solvency of developing countries is already spreading quickly among the punditocracy and major news outlets.

Given the weakened condition of wealthy states and corporations, the IMF will play a major role in any sort of multilateral bailout. Indeed the crisis presents an opportunity for the Fund to resurrect itself after a number of very, very bad decisions made in the Neoliberal 1980’s and 90’s finally came home to roost, bringing shame upon the organization and its ideas.

The question is what kind of an IMF will we get this time around? The critical work of Joseph Stiglitz, Ngaire Woods

, and others

has provided ample evidence that the Fund’s proclivities for anti-poor policies were not an accident, but a systematic result of the organization’s structure and culture.

Since 2002 (when such positions first gained widespread traction), there has been much talk of reform – a trend which will no doubt continue well past November’s Global Financial Summit – but precious little action.

The U.S. and Europe still retain a ridiculous share of the voting power within the IMF, World Bank, and the WTO, virtually guaranteeing that they will strong arm through whatever solutions they deem fit. While Ambassadors, Trade Representatives, and their ilk may talk a good game about promoting equality through increased multilateral liberalization, the bottom line is that truly equitable trade will not come about without a substantial sacrifice by the traditional “Great Powers” of the West. The recent trend of the U.S. and E.U. pursuing absurd schemes to evade accountability and transparency by undermining global forums also belies any rhetoric of good will.

Does the IMF have what it takes to bring about a true shift in the underlying structures of the global financial system? I doubt it, but it will be revealing to see just how hard Dominique Strauss-Khan (if he holds onto his job now that he has officially held onto his job despite a sex scandal) and his colleagues will try.

Sebastian Mallaby on the Bretton Woods Redux plans

October 20, 2008

Mallaby’s editorial in today’s WP echoes some of the broad points I tried to make in my last post, but goes into greater detail on some plausible concrete outcomes from the proposed Bretton Woods Redux.

The key points are in the following paragraphs:

So what might a new Bretton Woods conference usefully do? Well, it could reform the IMF, which has evolved from its original role into a rescue fund for collapsing currencies. During the emerging market crises of a decade ago, the IMF was central to all the bailouts. Its status has since dwindled…

Reestablishing the IMF as the agreed provider of bailouts would be a worthwhile project. The IMF puts economic conditions on its loans while governments place political ones; we don’t want to revive the cronyism of the Cold War, when countries from Cuba to Zaire could pursue absurd policies and know they would be bailed out because they were strategically useful.

The irony is that Britain and France will be the first to resist a serious effort to revive the IMF. British Prime Minister Gordon Brown talks vacuously about giving the organization the role of creating an early-warning system for crises, even though this is what thousands of economic forecasters already try to provide. What Brown does not stress is that serious IMF reform needs to begin with the modernization of its board. Rising powers such as China and India deserve more say. Declining powers need to give up some influence — and that includes France and Britain.

Like I said, we’re heading for Doha all over again…

Laying a new foundation for the global economy?

October 20, 2008

The Mt. Washington Hotel, Bretton Woods, NH, site of the creation of the current global economic governance arrangement (photo by robdebsgreen cc-by-nc-nd)

We have now seen first full week of trading since last weekend’s Euro-American attempt to stop the bleeding in the world’s financial markets. From any perspective, the results have been sobering.

Among the economic punditosphere, some consensus seems to be emerging (sweetheart bailouts = bad); however economists of various ideological stripes still offer competing explanations of the causes and effects of the crisis (for examples, see Tyler Cowen #1 and #2, Daniel Davies, and Arnold King), as well as a whole range of propositions about how to fix it.

Meanwhile, Mssrs. Bush and Sarkozy have announced plans to initiate a sort of Bretton Woods Redux at Camp David after the U.S. elections.

Taken together, these signs suggest that the captains of the global political economy may attempt to plot a bold new course in the coming months. Nevertheless, I remain suspicious that we’re really witnessing little more than a noisy shuffling of deck-chairs on a badly listing ship.

Certainly, the deluge of analogies linking the present era to the time when the Bretton Woods Conference was held are incomplete at best. The original conference did not happen at the first signs of global financial collapse (circa 1930-something), but rather in the midst of the resulting violence and global destruction of World War II (1944).

That era was one in which the U.S. and U.K. could quasi-legitimately claim to represent the core of the global financial system. The result was a naked demonstration of military and economic power thinly disguised as diplomacy. Richard Peet describes in his (richly detailed, but theoretically unsatisfying) book, Unholy Trinity: The IMF, World Bank and WTO how the outcomes of the New Hampshire meetings reflected their origins in back-room deals between U.S. Deputy Secretary of the Treasury Harry Dexter White and his counterparts working under Lord John Maynard Keynes. It was no coincidence that the resulting institutional arrangements so blatantly favored European and American interests. The event had been carefully engineered to ensure such an outcome.

What will the upcoming round of global economic talks look like? In a somewhat non-analytical, but nonetheless provocative piece published yesterday morning, DailyKos editor Devilstower gets to the heart of the matter. Here are three key quotes (emphasis added):

“While we are fretting about our plans to restore the broken economy, there’s one point that isn’t making the debates, and only rarely making the news. In many ways, we will no longer be the masters of our own economic ship. The factors that will most affect us in the future may no longer be under our control, or in the hands of those inclined to place our needs very high on their list of concerns.”

“After sixty years of Bretton Woods, the world is looking for a less dollar-centric alternative to our current fiscal system. And they’re not begging for our permission.”

“As the world meets in global summit to “rebuild capitalism,” the United States may host the event, but don’t expect the rest of the world to turn to America for ideas. Instead, they will try and sort out if we are AIG — salvageable, and possibly too large to fail — or Lehman Brothers — a former titan allowed to crash on the rocks.”

I agree with this assessment, although Devilstower’s claim that Europe will play a bigger role this time around ignores a more profound shift in the balance of global economic power. Given their current over-leveraged positions, the U.S. and the E.U. will be forced to cede some authority to the big players and creditors of the Global South (China, India, Brazil, Saudi Arabia, U.A.E. etc.). Thus, the analogy between the U.S. and AIG or Lehman is appropriate, but mis-specified: it will not be Europe that decides whether or not to make the call on this nation’s accumulated fiscal warrants.

My intuition is that these summits will look a lot more like the recently collapsed Doha round of negotiations at the WTO. In the foreground, the U.S. and European leaders will carry on a great shadow-play of magnanimity and cooperation. The opening gambit has already been made in the World Bank, where the U.S. has recently surrendered its long-cherished “right” to appoint the organization’s President.

At the bargaining table, however, these same U.S. and E.U. negotiators will flatly refuse to accept the fact that they are no longer the masters of the universe. Instead, they will bully, threaten, and backstab their way to a total impasse – or at best a watered-down statement of “principles” with no real institutional teeth to back it up (sound familiar?). This has been the pattern for a few years now, and I would be pleasantly surprised if it were to suddenly disappear when big issues made their way onto the table.

US will no longer appoint World Bank President

October 13, 2008

Wow.

The Guardian has the story.

This may be too little too late to mean anything in the context of the current financial crisis, but it is a very important step that was long overdue.

subscribe to my feed

subscribe to my feed