The IMF Reloaded…Remixed

April 10, 2009

Tony Curzon Price has a thoughtful piece at Open Democracy in which he examines what he calls The G20’s sins of commission.

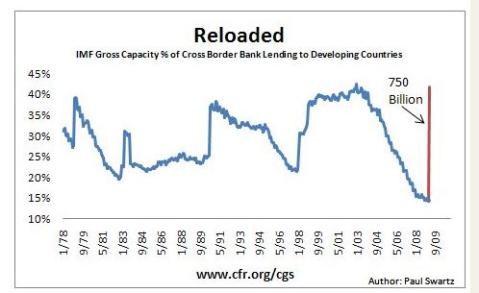

I’m interested in a whole bunch of angles that Price explores, but the money shot for all you global governance and development geeks out there is a graph Curzon Price recycles from Paul Swartz at Council on Foreign Affairs Geo-Graphics blog:

Curzon Price goes on to use the graph to make an interesting (and important) claim about the implications of China’s newfound romance with the IFI’s and global regulation.

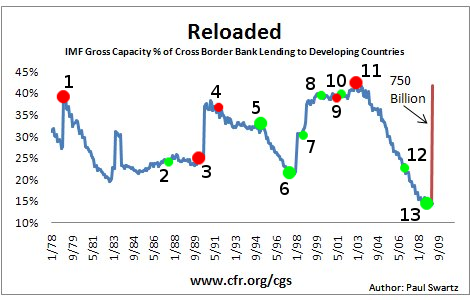

I, on the other hand, thought it would be kind of fun to play with the graph to try to get a better sense of what may have driven these changes in the IMF’s role over time. Since Swartz doesn’t share the data or source for his graphic, I’m reduced to hacking around with the .jpg in the GIMP (which made for a really fun distraction during a meeting the other day). Apologies for the resulting visual clutter, but here’s the same graph with some new knobs and bits. The bigger dots correspond to the events that accompanied the biggest shifts:

- Margaret Thatcher elected: May 1979

- Black Monday: Dec 1987

- Berlin Wall taken down: November, 1989

- Soviet Union Collapses: December 8, 1991

- Mexican Peso crisis: Dec 1994

- Asian Financial crisis: July 1997

- Brazil devalues the Real: Jan 1999

- Dot-com bubble bursts: March 10, 2000

- September 11, 2001

- Argentine debt default: Dec 2001

- US invades Iraq: March 20, 2003

- Brazil and Argentina pay off IMF debts: Dec. 2005

- Global Recession: October 2008

Some of the things I thought might correlate with sudden changes in the global weight of IMF lending – such as Black Monday (2); the Dot-com bubble burst (8); Argentina and Brazil paying off their debts (12) – didn’t seem to matter at all.

Others – such as Thatcher’s (and Reagan’s) election (1); the Mexican Peso crisis (5); and the 1-2 combo of the Asian (6) and Brazilian (7) financial crises – appear magnified when seen through this lens.

Most intriguing to me is the long steep slide that occurs following September 11, 2001 (9). My inclination is to explain that as the result of a perfect storm that combined the eroding credibility of the IMF (Joe Stiglitz, eat your heart out!) and a real estate derivative and petro-dollar fueled explosion of private lending world-wide. No matter how you slice it, though, there’s no denying that the world financial system has gone through some exceptionally dramatic changes in the last ten years.

Other than that, I don’t have a flashy Theory of Everything to explain all the data here. Heck, as I said, I don’t even have the data. Nevertheless, it’s fun to speculate.

Inequality in the Knowledge-Based Economy

December 17, 2008

I’m working on a short article about this topic and was crunching some World Bank Development Index numbers today.

The payoff for you, dear reader, is the following factoid of the day:

From 2000-2008, approximately $97 out of every $100 earned internationally from licenses or royalties was paid to a high income OECD country. In contrast, Latin American and Caribbean countries combined to earn $0.005 (yes, one half of one cent) out of that same $100.

Got that? $97 vs. $0.0o5!

The moral of the story: cheap laptops and broadband are only the tip of the iceberg.

Eat your heart out ICT4D community.

IMF swoops in with cash, conditionalities

October 29, 2008

Iceland and Hungary are the first recipients of IMF loans as a result of the current global financial crisis.

In a sign of what’s to come, the Fund is already demonstrating its continued willingness to impose policy conditionalities on borrower states.

The Guardian has the story in Hungary:

This week the International Monetary Fund stepped in to stop any more investors from pulling their funds out of the country altogether. Hungary is now set to become the first EU state to receive an IMF lifebelt – of around €12.5bn.

The bail-out announcement received a mixed response in Budapest yesterday. “We have a credit noose around our necks,” declared the rightwing daily Magyar Hirlap, while another paper showed bundles of forint notes being sucked up by a cyclone.

“This is going to be tough,” said the tabloid Blikk, pointing out that a condition of the loan would be a 300bn forint cut in public spending, which will likely lead to high inflation and attacks on social benefits.

And the Financial Times covers Iceland:

The application will be presented to the IMF’s board on Thursday and the central bank said a condition attached to the loan was for a rate rise to 18 per cent.

The move reversed a 3.5 per cent rate cut announced just two weeks ago by David Oddsson, central bank governor, underlining the influence the IMF now has over policymaking in Iceland.

Brian Coulton, managing director at Fitch Ratings, the credit rating agency, said Iceland’s central bank had “no choice but to work very closely with the fund”.

While the policy conditionalities attached to the loans appear less extensive than the intrusive demands the IMF and World Bank used to place on its borrowers, the persistent willingness of the Fund to dictate borrower fiscal policy suggest that the D.C.-based institution has failed to learn from experience. IMF-sponsored structural adjustment policies implemented throughout the 1980’s and 90’s precipitated a string of fiscal crises in the economies of the Global South.

While I’ll have to dig around in the academic journals to assess whether there’s any evidence that IMF-loans caused later crises among borrower countries in the 80’s and 90’s, the historical record in places like Argentina, Mexico, and Brazil is pretty clear: in the process of imposing conditionalities had profound flaws that facilitated the collapse of otherwise strong currencies.

The obvious difference this time around is that the borrowers are in Europe – it will be interesting to see how this affects outcomes.

Happy Open Access Day

October 14, 2008

Open Access (OA) FAQ

“Why support OA?” Because there’s nothing exclusive about ideas – we can share them at no cost and still develop business models to make a living. A vibrant knowledge ecology will thrive if we learn not to treat intellectual property regulations like legal cudgels to beat others into submission.

“Why does OA matter?” Because Access to Knowledge – whether in the form of software, academic journal articles, patented medicines, technical designs, or cultural products – will facilitate education, economic development, and equitable wealth distribution throughout the world.

But this is just a blog, you’re not really doing anything about OA: Actually, I use my blog to promote and enact OA principles (for example, check out my creative commons attribution-share-alike license up in the top of the right-hand sidebar). Also, as a graduate student and a researcher, I try to publish in venues that support OA models of distribution and licensing.

Alright, fine. I’ll “get involved,” just spoon-feed me some more information, please! For details about the day go here and here. If you really want to drink from the firehose, I dare you to subscribe to Peter Suber’s blog. If you still want to learn more about the theories and ideas behind OA, read this article by UC Berkeley law professor Amy Kapczynski, Yochai Benkler’s Wealth of Networks (don’t worry, it’s quick!), and Larry Lessig’s Free Culture.

Aaron, you rampaging nerd, I don’t read – just point me somewhere I can give money! Okay, fine. Support and get involved in the activities of the following organizations: Knowledge Ecology International, Public Knowledge, Universities Allied for Essential Medicines, Public Library of Science, and Essental Action (esp. their Access to Medicines project).

Anything else? Don’t forget to vote this November and please tip your waiter.

US will no longer appoint World Bank President

October 13, 2008

Wow.

The Guardian has the story.

This may be too little too late to mean anything in the context of the current financial crisis, but it is a very important step that was long overdue.

Why Politics and Institutions (Still) Matter for ICT4D: a reply to Ken Banks

September 29, 2008

This is a shameless cross-posting of my contribution to the Berkman Center’s Publius Project. In the essay, I respond to a piece published by Ken Banks last week (“One Missed Call,” see link below). If you have time, I highly recommend reading Ken’s piece first. I also recommend checking out the other excellent contributions to the project, which enjoys the expert guidance of Caroline Nolan at Berkman (thanks, Caroline!).

Ken Banks’ provocative contribution to the Publius Project, “One Missed Call” boldly urges the ICT for Development (ICT4D) community to look beyond bureaucracy-heavy, top-down solutions to global poverty and inequality. In a similar spirit, my response to Ken’s piece will take the form of a question, critique, and complementary challenge to the ICT4D community that runs somewhat afoul of the Easterly-Schumacher-inspired vision he offered.

Ken echoes William Easterly’s disdain for bureaucratic, large-scale approaches to global poverty, calling instead for the adoption of small techno-centric solutions based on principles of Human-Driven Design and deployment by “grassroots” NGO’s. Like Easterly, he encourages us to bet on the ingenuity of small-time entrepreneurs to break the world’s persistent cycles of poverty. If we identify these entrepreneurs, the theory goes, we can eliminate poverty without the immense waste and inefficiency that plague so-called “Big-D” development projects.

While both Easterly and Banks present compelling, attractive claims, they leave a key question unanswered: how can ICT4D advocates effectively confront the systemic and structural aspects of poverty or inequality within this framework?

Easterly’s argument takes for granted that well-positioned innovators can overcome institutional constraints at the regional, national and global levels. Indeed, his arguments in The White Man’s Burden closely resemble the work of free-market ideologues Milton Friedman and Friedrich Hayek insofar as he objects to all forms of developmental “planning” as fundamentally misguided. Empirical research in Development Studies contradicts this position, suggesting that the ability of grassroots NGO’s and others to deploy technological solutions effectively is overdetermined by the institutional environment within which they act (for a recent example, see Ha-Joon Chang’s Bad Samaritans – The Myth of Free Trade and the Secret History of Capitalism). Of course, to adapt Margaret Mead’s much abused phrase, I do not doubt that a small group of committed citizens can change the world. And yet, such changes are bound to be fleeting in the absence of broader interventions.

The problem, as I see it, stems from the fact that Easterly’s proposition is free-market economics with a friendly face – compassionate conservatism in the truest sense of the phrase. Embracing Easterly’s vision entails a radical denial that broad political, economic, and cultural structures determine developmental outcomes in any way. The history of global development since World War II offers numerous grounds on which to reject this claim. First of all, the emergence of the United States as a superpower influenced the creation of the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, the primary institutional frameworks within which development projects took place (until recently). Secondly, the concomitant dissemination of U.S. culture, values, and products has also shaped the ideals and aspirations through which people across the world understand what it means to be “developed.”

As a result, we cannot talk about “development” without referring to the broad political, economic and cultural currents that defined the late 20th century and the processes of globalization. All contemporary development projects operate in the institutional space defined by this history – and in many cases it is the space itself, rather than the any individual bureaucracy or top-down vision of change that determines what is and what is not possible for the poor and middle income populations of the Global South.

Contemporary global development paradigms (ICT4D among them) bear the traits of organizational and philosophical predecessors. The Millenium Development Goals represent a continuation of the Big-D development schemes of the 1950’s and 1960’s, where gigantic multilateral institutions like the United Nations dictated the terms on which the world’s poor would modernize. Similarly, the small-d development ideal proferred by Easterly and others places great faith in the ability of unregulated markets and small-scale entrepreneurs to bring widespread economic growth “from the bottom up.” This represents a scaled-down version of the so-called Washington Consensus of the 1980’s and 90’s that saw the dismantling of social welfare systems and the deregulation of financial markets around the world. The results of such “structural adjustment” were catastrophic for the poor, as local elites and multinational corporations extracted spectacular profits at the expense of less-empowered populations.

Both approaches – the big-D and the small-d – are stained by fundamental shortcomings that no amount of revisionism can wash away. On their own, neither will bring about sustainable widespread enhancements in the quality of life for the chronically poor and unstable regions of the world.

As a result, I challenge the ICT4D community to confront the contradictions of these competing paradigms of poverty and inequality alleviation.

At a practical level, we cannot simply abandon participation in (or engagement with) large national and multilateral political institutions. Access to fantastic gadgets and services will mean little in the long-run without a corresponding framework to support sustainable improvements in “human capabilities.” Likewise (and here I agree completely with Ken), the best intentioned multilateral efforts will fail unless they are grounded in the sort of modular, experimental approach embodied in Schumacher’s “small is beautiful” ideal.

Therefore, the ICT4D community (along with fellow travelers like myself) must find ways to split the distance between the Big-D and the small-d. We must reach out to the small grassroots NGO’s and innovators at the same time as we pursue less glamorous forms of political transformation and institution-building. We must design brilliant, appropriate gadgets and cultivate strong, accountable institutions. Together, these digital and social technologies will enable more people around the world to thrive, facilitating access to knowledge, networks, sanitation, water, and healthcare.

The need for broad political engagement has rarely been more apparent than in the present context. The collapse of the World Trade Organization’s Doha round of negotiations and the current global financial crisis provide textbook examples of institutional failures that grassroots intervention alone will not resolve. The lack of consensus at Doha reveals the extent to which existing global governance institutions have failed to meet the needs of low and middle income countries. Meanwhile, the implosion of the housing and credit markets in the United States has illustrated the risks of insufficient coordination between government and the private sector in the face of an obvious, long-standing threat to the collective interests of society. In the absence of sustainable solutions to these overlapping problems, rampant inequalities will likely reproduce and spread, leading to further financial and political instabilities.

In this setting, ICT4D advocates cannot afford to turn their backs on global institutions as critical mechanisms for achieving lasting techno-social change. Of course, analyzing and participating in big bureaucracies such as national states, multilateral governance forums, and international standards committees entails a distasteful degree of compliance with abusive forms of power. In this regard, Easterly’s claim that we must be wary of the tendency for these organizations to deliver corruption and inappropriate technologies is on target.

Nevertheless, if we want to avoid “missing the call” for technologies that have the potential to facilitate enhanced access, equality, and prosperity, such political and institutional engagement is more necessary than ever.

Globalization’s institutional collapse?

August 7, 2008

In response to the failure of Doha and the current global economic slow-down, two of Dani Rodrik’s most recent editorial pieces take the positions that #1: Doha was built on bad economic plans as well as ill-conceived negotiating strategies; and #2: the political and economic project of globalization currently suffers from a lack of intellectual consensus.

In the process, Rodrik points out the underlying problem with the existing global governance institutions:

There is no global anti-trust authority, no global lender of last resort, no global regulator, no global safety nets, and, of course, no global democracy. In other words, global markets suffer from weak governance, and therefore from weak popular legitimacy.

Is the lack of popular legitimacy just about weak governance, though? Clearly not – in order to obtain popular legitimacy, global governance institutions not only need to fulfill the functions listed above, but also to do so in an accountable way that integrates a semblance of democratic due process for the majority of stakeholders. These problems comprise Joseph Stiglitz’s famous “democratic deficit” and they are as much a part of Doha’s failure and the broader crisis of global institutions as the factors Rodrik enumerates.

In this sense, the broken consensus at the WTO also reflects the long-term costs of the G8’s constant maneuvering to undermine the institutional legitimacy of various multilateral fora.

More on Gurry Controversy and Brazil at WIPO

June 21, 2008

I just found out about the possible Brazilian-led challenge to Francis Gurry’s election as the new DG of WIPO a few hours ago.

Here are some interesting quotes (my translations) from news stories linked to by Joff Wild in the story I mentioned earlier.

This from the Agencia Estado coverage:

[Brazil’s Foreign Minister, Celso] Amorim, according to sources within his cabinet, admitted that the situation of the Australian [Gurry] could become unsustainable, as his placement could bring about a paralysis within the organization on account of the dispute between wealthy and poor [states].

Brazil, as a result, is inclined to re-open the debate over the vote. However, the chancellor does not exclude the possibility that the new director could come from a third country and not be the Brazilian Graça Aranha. The primary object of Itamaraty [Brazil’s Department of State], therefore, would be to guarantee that highest position overseeing the world’s patent system was occupied by someone sympathetic to the positions of emerging countries.

And the Folha de Sao Paulo (syndicated by Verbanet) reports that Gurry incurred the wrath of Amorim and the Lula government on account of his refusal to grant the second position at WIPO to Brazilian DG candidate Jose Graça Aranha (who lost to Gurry by 1 vote). Here’s a couple of good quotes from the story:

After spreading rumors that he would invite José Graça Aranha, who came in second in the voting…Gurry changed tactics. On Saturday, he offered a Brazilian diplomat a position in the third tier of the WIPO directorate, in the first formal attempt to pacify Itamaraty following its controversial nomination.

According to the Folha’s sources, Gurry said to the diplomat that he could not invite Graça Aranha to occupy one of the four vice-directorates of WIPO because he felt that this would give the Brazilian a platform from which he would try to undermine him.

All told, this sounds like a lot of cross-accusation and diplomatic shin-kicking. Nevertheless, I think it’s safe to say that none of it bodes well for Gurry’s ability to secure a strong mandate from a majority of the WIPO member states.

Anti-Counterfeiting Trade Agreement would stifle democracy, innovation, and development

March 20, 2008

If governed effectively, the trade in knowledge-based goods offers an historic opportunity to promote global prosperity. Medicines, information and communications technologies, and cultural resources (like books and music) all contain the promise of a better world where citizens, communities, and nations have access to the means of their own well-being. However, this promise brings immense responsibilities. The policy-makers and officials charged with overseeing the global trade of intellectual properties must balance competing claims in order to design effective governance systems. The recent actions of the Office of the United States Trade-Representative, the executive agency in charge of our national trade policy, reject balance, evidence, and democratic values in favor of elitist cronyism and corruption.

Since October of last year, the USTR Office, led by Bush administration appointee Susan Schwab, has sought to promote an “Anti-Counterfeiting Trade Agreement” (ACTA). In public documents and statements, Schwab’s office has claimed that ACTA will promote the sustainable development of the world economy and international cooperation by “fighting fakes.” These claims lack any empirical grounding. As proposed, ACTA will neither encourage economic growth nor cooperation. Instead, ACTA will stifle democracy, development and innovation by creating an exclusive, ineffective agreement outside of the multilateral institutions that govern global trade. As a result, ACTA threatens the interests of the United States and the world and it ought to be abandoned immediately.

The Office of the USTR has not been forthcoming with substantive information about the details of ACTA. This lack of public information is both alarming and disgraceful in a democratic society. However, even the few existing arguments the USTR has made in favor of the agreement do not withstand rigorous scrutiny. For example, the USTR’s ACTA “Fact Sheet” begins with the following statement:

The proliferation of infringements of intellectual property rights (“IPR”) particularly in the context of counterfeiting and piracy poses an ever-increasing threat to the sustainable

development of the world economy.

This assertion – that counterfeiting and piracy threaten economic development – ignores current research on the nature of knowledge-based assets, IP-related trade, and innovation practices in the global economy. Numerous academic experts in the fields of economics, law, sociology, business, and political science have produced empirical analyses that undermine these claims. Furthermore, a growing consensus of legal and policy experts agree that the current system of strict IP-enforcement endorsed by the USTR does not serve the public interest. The fact that the USTR retains a myopic focus on devoting additional time and resources to strengthening enforcement reflects the office’s inability to incorporate diverse perspectives into its policy-making process. Alternative models of IP regulation and management exist that can distribute wealth, knowledge, and intangible assets more efficiently. The USTR ignores these alternatives at the peril of the economic prosperity of the United States and the world as a whole.

The “Fact Sheet” goes on to claim that international cooperation should play a crucial role in promoting economic development and safety through IP-related trade. Yet, the actions of the USTR on ACTA contradict this position. In the absence of widespread support for ACTA in public global governance forums such as WIPO and the WTO, the USTR has opted to pursue closed negotiations and consultations with wealthy states and industry lobby groups that stand to benefit from strict IPR regimes. In the process, the USTR has turned its back on transparent and accountable policy-making in public institutions. The USTR has also unilaterally denied governments, civil society groups, academic experts, corporations, and citizens who disagree with the “strict IP enforcement” approach a seat at the bargaining table. Instead of a truly cooperative, democratic, and deliberative dialogue on IP regulation, the USTR has embraced cronyism and corruption

In order for IP-related trade reform to produce sustainable economic growth and development, the USTR should puruse a much more transparent and democratic approach. This means that the USTR must not create policy in a narrow-minded echo chamber, but through inclusive, deliberative process where all of the stakeholders have an equal ability to influence the outcome of the debate. The US government, other wealthy states, and a handful of large private firms can no longer act as though they have a natural right to unilateral decision-making. More than ever, the possibility of global security, prosperity, and well-being depends upon the ability of the United States to embrace truly democratic due process. The knowledge-based economy will not produce public goods unless a broader public has a say in its control.

As a result, I recommend that the USTR take immediate action to ensure that the following three conditions for all future negotiations on IP governance and regulation are met:

(1) Abandon all efforts to pass ACTA and bring negotiations on future IP-related trade agreements into the global governance institutions where they belong. WIPO and the WTO remain far from democratic or public in many ways, but they represent a critical improvement on the fractious, power-politics embodied by ACTA as it exists today.

(2) Publicly recognize that strict enforcement of the existing, broken IP system does not advance the interest of the United States or the rest of the world. The USTR currently pursues a blinkered approach to IP policy. Part of the reason the gray-market in unlicensed reproductions of patented, copyrighted, and trademarked goods thrives around the world is that existing IP laws contradict legitimate social needs. By ignoring these issues the USTR does not make them go away. The United States and the world require a more forward-thinking policy and a public statement to this effect would be a positive first step towards meeting this need.

(3) Increase opportunities for substantive public participation in USTR policy-making and agenda-setting. Currently, the USTR values the interests of a small minority of the country’s businesses at the expense of other firms and many millions of its citizens. The existing approach of closed-door meetings with industry lobby groups will not suffice to correct this problem. The USTR should regularly hold open public fora, debates, and hearings on trade-related issues in locations around the country. All possible steps should be taken to ensure that diverse perspectives on US trade policy are represented in these settings and that the USTR takes these perspectives into account. The office must also make available more substantive information on existing policies and proposals.

This extended post is the rough draft of the public comment I plan to submit to the Office of the United States Trade Representative on the proposed “Anti-Counterfeiting Trade Agreement” (ACTA). If you want to submit your own comment, please go here for details. If you are unfamiliar with ACTA, I have written about it in earlier posts (start here and here). Those posts contain useful links to outside sources and additional information. I am also making the “fact sheet” about the proposed agreement published by the USTR available here (PDF). If you prefer to get your facts straight from the USTR, you can find the same document on their site (PDF).

ACTA – An End-run Around WIPO

March 9, 2008

Following up on a pointer from Peter Evans in response to my last post, I came across this old announcement on the website of the US Trade Representative.

Turns out the US, EU, Japan and other wealthy nations have responded quite aggressively to the success of the Development Agenda at WIPO. Less than two weeks after the WIPO general assembly voted to make a permanent committee on the development agenda, the wealthy states countered with the creation of a new “Anti-Counterfeiting Trade Agreement” (ACTA).

Based on the trail of celebratory press releases (the USTR’s is here, the EC’s is here, and the International Trademark Association’s is here) and a highly un-informative fact sheet (PDF) from the USTR, this promises to be some spectacularly old wine in a new bottle. Everybody promises that this will bring an end to evils of piracy and will restore lost millions to poor, unfortunate industry executives. I’m sure the authors of the agreement are already lining up celebrity endorsements…

So, what does this mean for WIPO and the fate of the development agenda? Michael Geist blogged the original announcement back in October and he hits the nail on the head:

“Given the recent backlash at WIPO, the U.S. is avoiding the U.N. system. Instead, it has created a new counterfeiting coalition of the willing that includes the European Union, Japan, South Korea, Mexico, New Zealand, and Canada. Those countries yesterday simultaneously announced enthusiastic support for a new trade agreement with negotiations to begin next year. Indeed, International Trade Minister David Emerson’s announcement to the House of Commons brought the MPs to their feet.

This treaty could ultimately prove bigger than WIPO – without the constraints of consensus building, developing countries, and civil society groups, the ACTA could further reshape the IP landscape with tougher enforcement, stronger penalties, and a gradual eradication of the copyright and trademark balance.” (emphasis added)

And people wonder why the Doha Round of the WTO hasn’t gone anywhere? This is the ultimate in bad faith bargaining and deserves to be called much worse. Essentially, the wealthy OECD countries and a few of their friends have turned their backs on the possibility of building inclusive and accountable global institutions in favor of creating yet another regulatory thicket of privately negotiated strict IP enforcement rules. There are so many reasons that this is a bad idea that I don’t even know where to start.

To make matters worse, if we take the rhetoric of the USTR and the EC at face value, they are embracing an outmoded vision of the IP ecosystem in which “counterfeiting” (a.k.a. reproducing stuff) is inherently bad for business. This kind of moralizing and polarizing talk is counterproductive, but a moralizing and polarizing treaty between the most powerful and wealthy nations in the world would be a whole lot worse.

If there’s any silver lining to this cloud, it’s that the agreement doesn’t exist yet. I’ll say more in my next post about an opportunity to do something to prevent it.

subscribe to my feed

subscribe to my feed